50% Profit is Possible Even Without BPS

"It’s been a real eye-opener as to where the effort needs to go, and it wasn’t what I thought."

Ian Davis, of Holwell Court Farm, opens his books, and tells of the discovery that a 50% gross profit could be achievable by out-wintering cattle. "It’s been a real eye-opener as to where the effort needs to go, and it wasn’t what I thought." Read the synopsis below, or, watch him tell his story on YouTube.

The Challenge

Sheila had challenged me last week to have a look at how much we spend as a direct result of housing our cattle over Winter, and what the impact would be if we were able to out-winter them.

Surprise: Half Our Costs Go To Winter Feeding!

It’s been a surprising insight as to how much it does cost to house our cattle. I never questioned housing our cattle in winter because we have been doing it for so long.

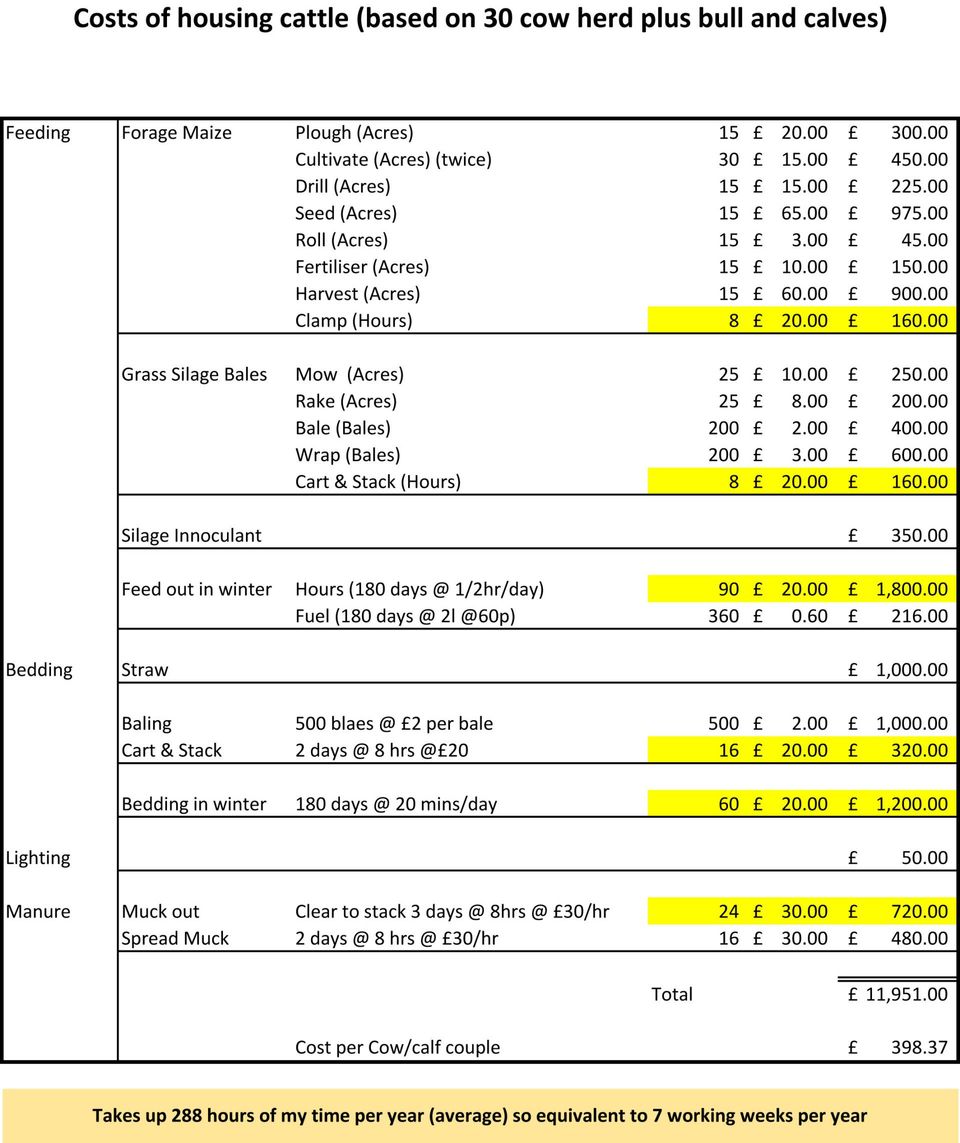

This first worksheet uses the low end of contractors’ rates, rather than figuring out the details, and putting in my time at £20 an hour. I chose that rate because that’s roughly what I can earn when I do other work off the farm. I was quite surprised that for our small herd of 30 cows, the over-wintering cost works out to nearly £12,000. We sold store calves last Friday and they averaged £845, and about half of that has gone to the cost of Winter housing and feeding.

Would Direct Drilling the Maize Lower Cost?

Forage maize is not good in terms of its impact on soils, because it leads to bare ground between the rows for much of the year. For the last two years, I’ve been under-sowing with grass to try and protect the soil, and get us quickly back ready to graze the field again.

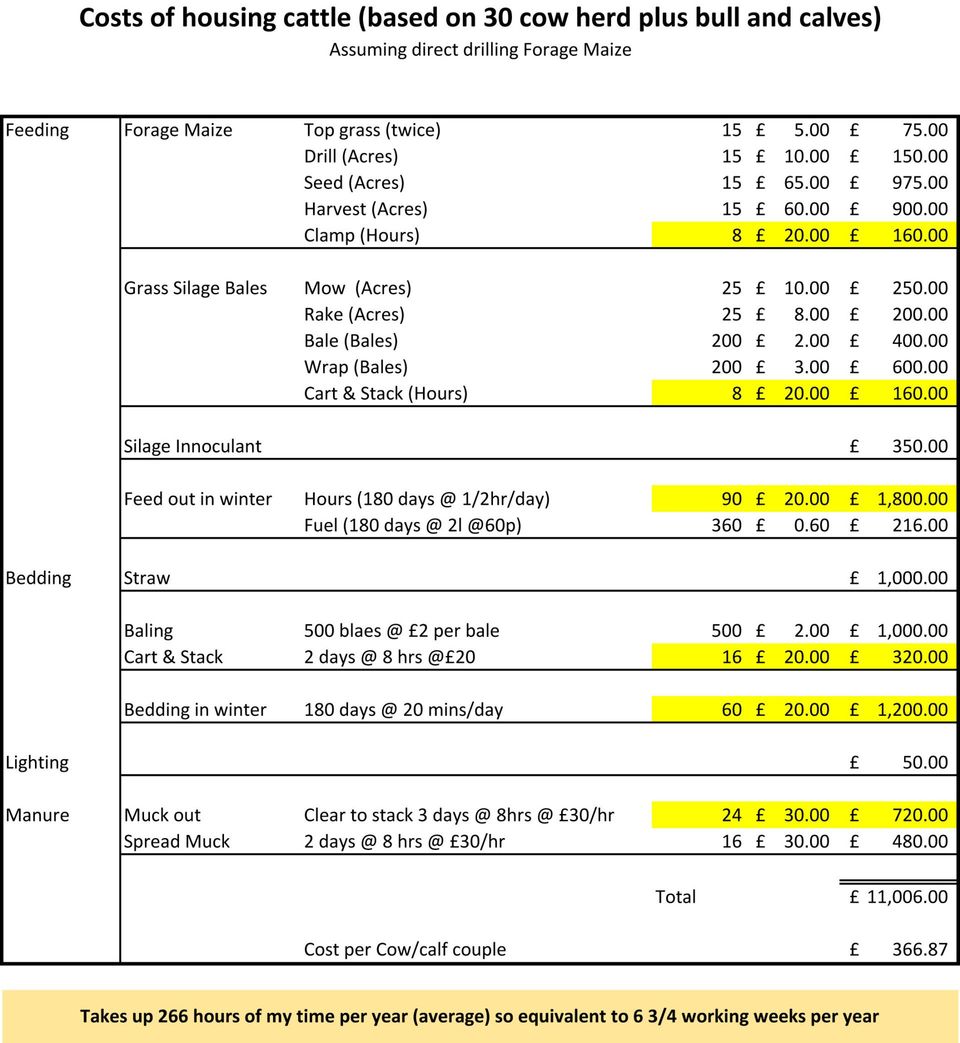

I was mulling over in the last few months taking that a step further, which is what is listed below. Instead of cultivating the ground, the big difference here is on the maize. It’s based on mowing the grass twice to subdue the grass so it doesn’t compete with the maize, and then direct drilling the maize.

I had been thinking this could be quite a step forward, and would make a big difference. When you actually look at the cost impact on winter housing costs, the actual difference is quite marginal.

Key Insight: Focus on Quality of Soils

What the whole exercise has brought to life for me is that my time and my ingenuity would be far better spent focusing on the quality of our soils. We need to focus on getting our pastures that we graze into the right condition so that we can out-winter using holistic planned grazing without causing significant damage to our soils while we’re at it. Any changes I try to make in producing our Winter feed are just tinkering around the edge.

7 Extra Weeks!

Another item I noted was that quite a bit of my costs derived from my time feeding and bedding animals during housing. I’m looking at 6.5 to 7 weeks of my time each year spent on housed cattle, based on standard 40-hour working weeks. When you think what else you could do with 7 extra weeks suddenly appearing in the year, it’s quite a thought.

50% Profit is Possible, Even Without BPS

If we were able to out-winter, grazing a forage reserve, cut something like £400 from our cow-calf pair costs, that would be roughly double what we receive in the Basic Payment Scheme subsidy on our farm per acre grazed. This would mean that even if we stopped receiving subsidies at some point in the near future, we would still stand a reasonable chance of achieving a 50% profit on the business; whereas we’re running somewhere in the region of 10%, before we started moving into the holistic planned grazing approach to things.

The whole process didn’t take that long to do, and it’s been a real eye-opener as to where the time needs really to be applied, and where the effort needs to go, and it wasn’t what I thought.